SHUTTING OFF GREEN AND CHEAP RENEWABLE ENERGY IS A COUNTERINTUITIVE PRACTICE THAT HAS BEEN WIDELY DISCUSSED AND USUALLY CRITICIZED IN THE PAST. USUALLY, THIS DISCUSSION FOCUSES ON THE SO-CALLED CURTAILMENT (EINSPEISEMANAGEMENT OR EINSMAN) BY GRID PROVIDERS (TSO/DSO), WHO OCCASIONALLY CURTAIL RENEWABLES TO STABILIZE A GRID THAT IS UNABLE TO TRANSPORT ALL OF RENEWABLE PRODUCTION. ACCORDING TO THE BUNDESNETZAGENTUR THIS KIND OF GRID CURTAILMENT AMOUNTED TO 5.818 GWH IN 2021 AND CREATED COSTS OF 807 MIO. EUR. HOWEVER, THERE IS A SECOND, PURELY ECONOMIC REASON TO SWITCH-OFF RENEWABLE ENERGY PRODUCTION AND DATA AS WELL AS EXPERTISE ON WHY AND HOW THIS HAPPENS IS HARD TO COME BY. WE WILL USE THIS BLOG TO SHED LIGHT ON THE BUSINESS LOGIC OF ECONOMIC RENEWABLE CURTAILMENT IN ORDER TO STRUCTURE THE LOGIC BEHIND A DEBATE THAT HAS BEEN THE CAUSE OF TORN OUT HAIR IN MANY COMPANIES INCLUDING OUR OWN.

A quick disclaimer at this point: We wrote this article for internal purposes and for market partners, so if you don’t want to dive this deep, maybe it’s time to stop reading here. For the nerds: let’s go!

Renewable Curtailment and the Merit Order

Following the merit order logic, renewable producers (especially wind and solar) should be the last technologies to leave the market as they essentially have short run marginal production costs of zero. If you’re green enough, you know the slogan “the sun doesn’t send you a bill”. Spoiler alert: it does, however more of a one-time entry bill rather than a monthly invoice, but I digress…

We understand that renewables (and nuclear) sit at the front of the merit order stack producing irrespective of current spot prices while flexible generation, such as coal, gas and pumped hydro react to short-term prices and cover residual demand. However, the non-renewable production is not fully flexible and has a quite large so-called must-run element. In 2020 my quick analysis showed that even at very negative prices they had a must-run capacity of around 16 GW, which will not shut off in the short run, even if they must pay to run. There are many reasons for this, but I won’t get into them here.

Economic Curtailment in Practice – Easter Monday 2020

So what happens on a day with low demand and with very high renewable production with all non-renewable flexibility running at its minimum must-run level? Let’s have a look: A classic time for this are the Easter holidays, as there is very little industrial demand and the Easter bunny likes it sunny. On Easter Monday in 2020 at 3pm, renewable production from wind and solar was forecast at 47 GW while total demand was forecast at 46 GW. We have a situation, where supply > demand. This indicates a residual load of 46 GW – 47 GW = -1 GW. In such a situation, either demand must increase, or production needs to shut off. Something must give. Don’t forget that we have 16 GW of must run capacity so actually 17 GW has to give…

What about prices? Well, prices in this instance do what prices are supposed to do: They signal an abundance of supply and they’re not subtle about this. Prices i.e. in hour 3-4pm were at a negative level: -78 EUR/MWh. This means that in this single hour, producers were willing to pay 3.6 million EUR to customers to take their product. Looking at the graph, you can see prices, load forecast, residual load, wind + solar forecast and wind + solar actual production. Take a second to have a look.

Curtailment at negative prices

The keen observer might have noticed that actual wind and solar production were significantly lower than forecast production during the hours with the lowest residual load and the most negative prices:

Roughly 10 GW of Wind and Solar curtailed at 3pm

It could have been the case that the weather forecast was just wrong on this day and that they delivered less than expected, however, this is not the case here. These plants decreased their production by roughly 10 GW rather voluntarily. Why would they do this, you might ask? However, the better question is: why haven’t they done this before? Why would they produce at negative prices at all and pay to produce power; and secondly, why should they shut only down production in a range between -50 EUR/MWh and -80 EUR/MWh exactly? This question draws us into the mind-numbing business logic of renewable curtailment.

Business Logic of Renewable Curtailment in a subsidy-driven Environment

There are three parties to this game: The renewable producer/asset owner (Ms. Solar), the power trading company, e.g. yours truly, (Mr. Trader) and the DSO (Ms. DSO). Within the market premium model, Ms. Solar receives revenues from two sources: Mr. Trader and Ms. DSO. Ms. DSO pays Ms. Solar the market premium for each hour of the month, except when §51 EEG kicks in. More on this later. The trader is the key decision-making agent in this game, as they usually have control over the asset and make the decision over whether the plant should be curtailed or not.

Case 1: no §51, Ms. Solar receives the reference market value for her asset from Mr. Trader and the market premium from Ms. DSO

Assumptions:

- Subsidy level (anzulegender wert) = 90 EUR/MWh

- Reference market value = 30 EUR/MWh

- Market premium = government subsidy level (anzulegender Wert) - reference market value Solar, therefore market premium = 60 EUR/ MWh

- Administrative curtailment cost = 10 EUR/ MWh - shutting down a plant causes a lot of invoicing and measurement headaches, so we will give this a cost.

- Full compensation condition of Ms. Solar: This assumption is crucial as contracts between Ms. Solar and Mr. Trader can be structured in many ways. However, we assume a smart contract design. Mr. Trader guarantees Ms. Solar that he will fully compensate her for any lost revenues in case of curtailment measures. This is crucial, as Mr. Trader is the one in charge of making any curtailment decisions and therefore Ms. Solar should only agree to be curtailed if she is guaranteed that she is never worse off when being curtailed.

Curtailing at positive prices (don't try this at home)

Let us look at the revenues with and without curtailment for Ms. Solar and Mr. Trader in a case where market prices are at a positive level of 110 EUR with all assumptions (above) in place.

If there is no curtailment, Ms. Solar receives 60 EUR from Ms. DSO and 30 EUR reference market value solar from Mr. Trader putting her at 90 EUR. However, if she is curtailed, she will still receive her 30 EUR power payment from Mr. Trader (with as-if production measured in a previously agreed manner[1]) but also the trader will need to compensate her 60 EUR for lost payment from Ms. DSO, which she will not receive as Ms. DSO only pays her when she actually produces. This again puts her at 90 EUR, so she will not care if she is curtailed or not.

For Mr. Trader, the picture looks different. If he does not curtail he has to pay 30 EUR in reference market value to the producer, but he will receive 110 EUR for the power he sold on the market. So he makes 110 EUR – 30 EUR = 80 EUR. Check illustration 1 for this. If he curtails the power, he cannot sell the power on the market, so he receives no money there. But he has still needs to pay the 30 EUR in power payments to the producer and in addition compensate her 60 EUR for the lost revenues from Ms. DSO. Furthermore, he accrues administrative curtailment costs of 10 EUR. This would put him at a revenue of -100 EUR. Check illustration 2 for this scenario. Comparing his decision between not curtailing and curtailing he would make a loss of:

Value of curtailment decision = revenue with curtailment – revenue without curtailment

= -100 EUR – 80 EUR = -180 EUR.

Clearly, the trader is a lot worse off if he chooses to curtail; therefore, he will not make this horrible decision. Have a look at illustrations 1 and 2 and the table to understand this point.

Illustration 1

Illustration 2

market price = 110 EUR | Ms. Solar | Mr. Trader | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Header | revenue w/o curtailment | revenue with curtailment | revenue without curtailment | revenue with curtailment | value of curtailment |

payment from Ms. DSO | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

power payment from Mr. Trader | 30 | 30 | -30 | -30 | 0 |

compensation payment from Mr. Trader | 0 | 60 | 0 | -60 | -60 |

market revenue trader | 0 | 0 | 110 | 0 | -110 |

curtailment cost trader | 0 | 0 | 0 | -10 | -10 |

sum | 90 | 90 | 80 | -100 | -180 |

Curtailing at very negative prices

Now let’s look at the same setup when market prices drop down to -90 EUR. For Ms. Solar, everything stays the same. She does not care whether she is curtailed or not, because she will always receive her 90 EUR in income. However, once more for Mr. trader the story changes. If he does not curtail, he pays 30 EUR to the producer, however he receives a price of -90 EUR for the power at the market i.e. he has to pay 90 EUR for selling his power. This puts him at a revenue of -120 EUR if he produces. See illustration 3 for this. If he curtails on the other hand, he has to pay the 30 EUR in reference market value, the 60 EUR in compensation and the 10 EUR in administrative curtailment cost. But he foregoes paying the -90 EUR in market prices as he does not sell anything. This puts him at -100 EUR. See illustration 4 for this. The value of the curtailment cost is calculated as below.

Value of curtailment decision = revenue with curtailment – revenue without curtailment

= -100 EUR - (-120 EUR) = 20 EUR

Now Mr. Trader is actually 20 EUR better off when he curtails the power than when he produces. Therefore, he will curtail. The table and illustrations 3 and 4 below indicate the revenues for Ms. Solar and Mr. Trader in the case of highly negative market prices.

Illustration 3

Illustration 4

market price = -90 EUR | Ms. Solar | Mr. Trader | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Header | revenue w/o curtailment | revenue with curtailment | revenue without curtailment | revenue with curtailment | value of curtailment |

Payment from Ms. DSO | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Power payment from Mr. Trader | 30 | 30 | -30 | -30 | 0 |

Compensation payment from Mr. Trader | 0 | 60 | 0 | -60 | -60 |

Market revenue trader | 0 | 0 | -90 | 0 | 90 |

Curtailment cost trader | 0 | 0 | 0 | -10 | -10 |

Sum | 90 | 90 | -120 | -100 | 20 |

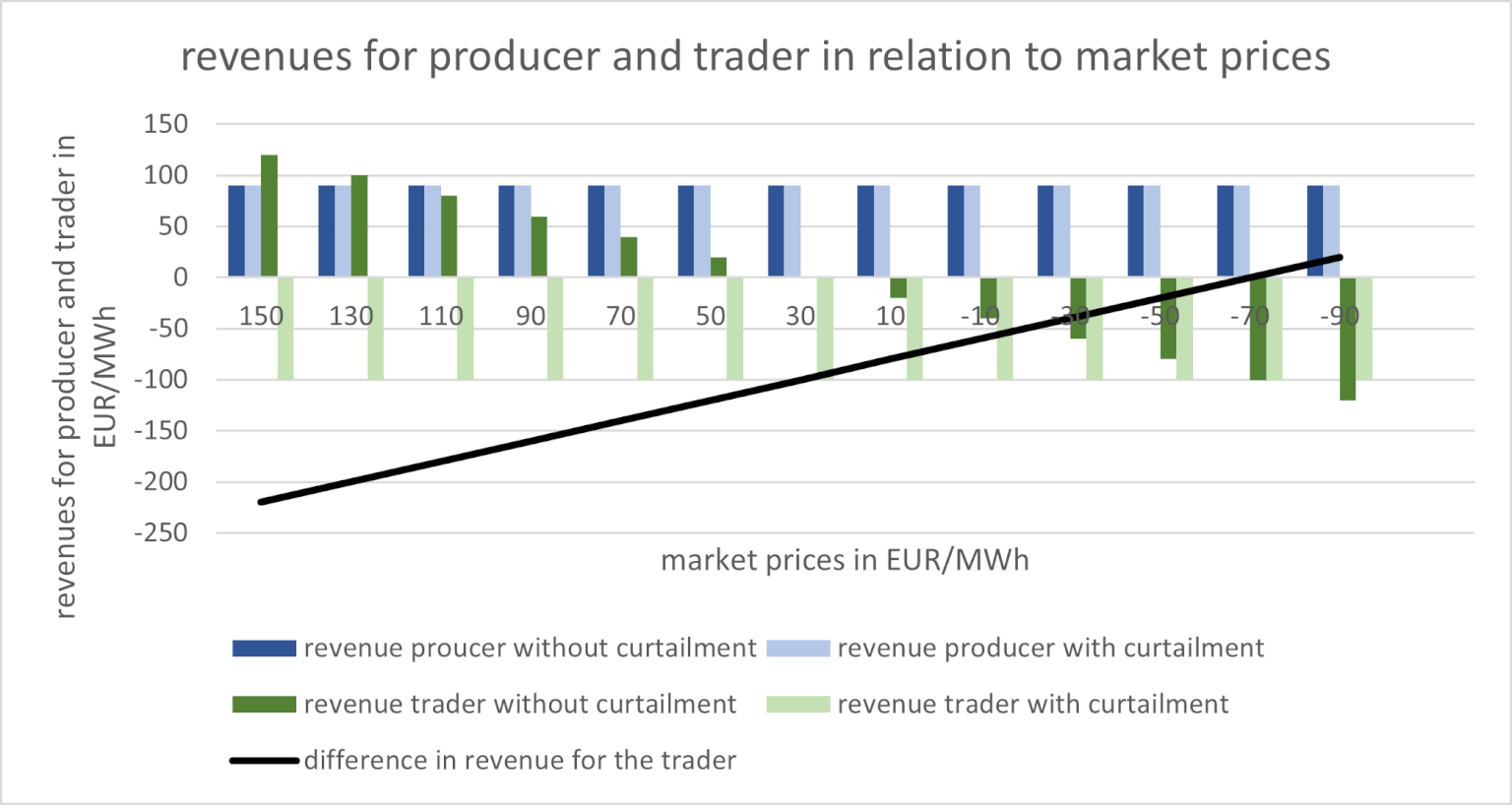

General curtailment value of Mr. Trader and Ms. Solar

So, the question is, when does Mr. Trader curtail? The graph 1 below shows the revenues to Ms. Solar (always stable) and Mr. Trader for different market prices given the decision to curtail or not. The black line indicates the value of the choice to curtail by Mr. Trader. You can see how in a reference market contract, the revenues of Ms. Solar are always flat, while the revenues of Mr. Trader fluctuate. The prices on the X-axis were chosen to have an average value of exactly 30 EUR. Therefore, Mr. Traders revenues are exactly flat if he does not curtail over these prices, as he receives 30 EUR on average and pays out 30 EUR to Ms. Solar. As Mr. Trader wants to survive, he will charge a Management Fee for his services, which I ignored for this article as it would unnecessarily increase complexity.

Graph 1: Revenues depending on market price levels

Let us do some math to evaluate Mr. Trader’s choice and see when he curtails. He does so when his revenue of curtailing is higher than the revenue without curtailing:

Trader revenue without curtailment = - power payment from trader + market price

Trader revenue with curtailment = - power payment from trader – compensation payment from trader – curtailment cost

Where,

Power payment from trader = reference market value

(This payment does not have to be the reference market value. Power payments could also be hourly spot prices depending on the contract arrangement between trader and producer. More on this later)

Compensation payment from trader = market premium = subsidy level – reference market value

Curtail if:

Trader revenue with curtailment > Trader revenue without curtailment

- power payment from trader – compensation payment from trader – curtailment cost > - power payment from trader + market price

The power payment from trader cancels out, so we get:

– compensation payment from trader – curtailment cost > market price

So, the trader curtails when market prices fall below what he needs to pay in compensation plus the added curtailment cost. Plugging in the values for the compensation payment we get a choice to curtail if:

-(subsidy level – reference market value) – curtailment cost > market price

Filling in the number for the previous case:

-(90 EUR – 30 EUR) – 10 EUR >= market price

The trader will curtail whenever prices fall below -70 EUR, which is exactly what happened on the Easter Monday described above.

The insight behind this is clear: When subsidy levels are high, curtailment happens at lower prices, as Mr. Trader needs to make high compensation payments. If the reference market value increases to very high levels, the compensation payment decreases as the foregone payment by Ms. DSO decreases a lot. This is why in 2022, when price levels increased to very high levels, renewable plants were shut down at only slightly negative prices, because Mr. Trader did no longer need to compensate Ms. Solar for their foregone DSO payments as these had decreased to zero. We have a blog post on curtailment decisions in various price scenarios and the possibility of curtailment at positive prices if the subsidy turns negative as is the case in a CfD. But no more on this here.

The general rule is to curtail whenever prices are lower than the compensation payments from Mr. Trader to Ms. Solar

Case 2: A subsidy-free World where §51 holds: Ms. DSO pays nothing, while Ms. Solar receives the Reference Market Value for her Production from Mr. Trader

Now, let us move on to the case in which §51 holds. §51 EEG says that there will be no payment of the market premium if day ahead spot prices are negative for 4 or 6 consecutive hours (depending on the age of the plant). Basically §51 puts us into a situation without government subsidies.

All assumptions from above stay the same only that now Ms. Solar cannot expect a payment from Ms. DSO. The law says that these payments will not need to be made if prices are negative for a while. This case shows us the behavior of Mr. Trader in a subsidy free world.

Curtailment decision at slightly negative prices

Without curtailment, Ms. Solar only receives the power price, which here is still set to be the reference market value of 30 EUR. If she is curtailed we still want to put her into the same position as without curtailment. Hence, Mr. Trader must compensate her for the reference market value if he curtails.

Mr. Trader’s situation also only changes from the one described in Case 1 by the fact that, if he curtails, he no longer needs to compensate Ms. Solar for the lost revenues from Ms. DSO. Let’s have a look at a situation where market prices fall to -20 EUR, a situation in which Mr. Trader would not have curtailed in the previous case.

Ms. Solar receives 30 EUR either way, so her revenue does not depend on the curtailment, however she no longer receives the market premium from Ms. Solar, so she is clearly worse off without the subsidy.

If Mr. Trader chooses not to curtail, he pays 30 EUR in reference market value and a market price of -20 EUR. In this case, he makes a loss of 50 EUR. See illustration 5 for this. If he chooses to curtail on the other hand, he still needs to pay out the 30 EUR with an additional 10 EUR of curtailment costs. See illustration 6 for this. However, he needs not to pay the negative market prices and there is no longer any compensation payment for the DSO payments. So in the curtailment case he makes a loss of 40 EUR.

Value of curtailment decision = revenue with curtailment – revenue without curtailment

= -40 EUR – (-50 EUR) = 10 EUR.

Therefore Mr. Trader already creates value of 10 EUR by curtailing the asset at a price of -20 EUR.

Doing the math for this case yields the same logic as above.

Trader revenue without curtailment = - power payment from trader + market price

Trader revenue with curtailment = - power payment from trader – compensation payment from trader – curtailment cost

Where,

Power payment from trader = reference market value

Compensation payment from trader = 0

Curtail if:

Trader revenue with curtailment > Trader revenue without curtailment

- power payment from trader– curtailment cost > - power payment from trader + market price

The power payment cancels out, so we get:

– curtailment cost > market price

The table and illustrations 5 and 6 show these points.

Illustration 5

Illustration 6

market price = -20 EUR | Ms. Solar | Mr. Trader | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Header | revenue w/o curtailment | revenue with curtailment | revenue without curtailment | revenue with curtailment | value of curtailment |

Payment from Ms. DSO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Power payment from Mr. Trader | 30 | 30 | -30 | -30 | 0 |

Compensation payment from Mr. Trader | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Market revenue trader | 0 | 0 | -20 | 0 | 20 |

Curtailment cost trader | 0 | 0 | 0 | -10 | -10 |

Sum | 30 | 30 | -50 | -40 | 10 |

The graph 2 below indicates the revenues of Ms. Solar and Mr. Trader in a subsidy free world. You can see that compared to the situation in Case 1, Mr. Trader would curtail the plant much earlier and if you wish, at more reasonable prices. Also note that the revenues at positive values on the X-axis are hypothetical as by definition §51 only kicks in once prices are negative.

Graph 2: Revenues depending on market price levels

In a world without subsidies, traders will curtail whenever market prices drop below their administrative curtailment costs. If we assume curtailment costs to be at zero, renewable power would be curtailed at a price of zero.

The magic formula remains. Curtail whenever:

– compensation payment from trader – curtailment cost > market price

Curtailment Decisions in a Spot Price Payment Contract

To dive even deeper into the subject, there are many who claim that this choice structure changes when we move from a situation in which Mr. Trader pays Ms. Solar the monthly reference market value, as in the example above, or whether the trader pays the producer hourly spot prices. We have a blog article on why we believe that paying hourly spot prices is a far superior contract model than paying reference market values, however no more on this here. The main difference between the models is that in the spot price model, Mr. Trader pays Ms. Solar the hourly value of her production rather than a fixed monthly average value. Generally, the revenues for both sides will not change over the course of a month.

In the case of curtailment decisions, however, the choice architecture for the trader is not at all influenced by the question whether he makes a monthly average payment (reference market value) or an hourly payment (Spot prices) to Ms. Solar, because the power payments from Mr. Trader to Ms. Solar are simply not part of the magic curtailment formula. Curtail if:

– compensation payment from trader – curtailment cost > market price

Spot price contract - curtailment in Case 1 with very negative prices and a market premium level of 60 EUR

In the case of a spot payment contract, Ms. Solar still receives a payment of 60 EUR from Ms. DSO in when she produces. However, she now receives the hourly market price from Mr. Trader which is -90 EUR. This puts her at a revenue of -30 EUR. At first glance this looks like a bad deal for Ms. Solar compared to the previous case with reference market values where she made 90 EUR. However, this misses the point as she will make this money back receiving much higher revenues compared to the reference market situation in case of positive prices. See Graph 3 and compare to Graph 1 to make sense of this point. If she is curtailed, again she needs to be put into the same financial situation making her indifferent between being curtailed or not. So in case of curtailment, she receives a compensation payment from Mr. Trader for the lost 60 EUR of revenues from Ms. DSO. In addition, she receives a compensation “payment” of -90 EUR from Mr. Trader. It may seem counter intuitive that Ms. Solar needs to pay Mr. Trader for power she did not produce. But again, the crucial point is that she is indifferent between being curtailed or not. So in the curtailment case, she has a revenue of -30 EUR.

The situation for Mr. Trader looks different again. In the case of production, he receives a market payment of -90 EUR from the market i.e. he pays 90 EUR for selling his power. He “pays” a power payment of -90 EUR to Ms. Solar i.e. he receives these 90 EUR. So without curtailment, Mr. Trader has a flat revenue of 0 EUR. See illustration 7 to grasp this point. That is generally the case for Mr. Trader in a Spot contract. His revenues are always flat as he only passes market prices onto Ms. Solar. If he decides to curtail, he now has to compensate Ms. Solar for the lost 60 EUR of payment from Ms. DSO. However, he still "pays" the -90 EUR in power payments to Ms. Solar i.e. he receives this money. In addition he has curtailment costs of 10 EUR putting him at a revenue of 20 EUR. Hence, just like in Case 1, where Ms. Solar receives the reference market price, Mr. Trader is 20 EUR better off by curtailing at very negative prices. See illustration 8 to understand this point.

The table and illustrations 7 and 8 below showcase this situation of case 1 (no §51, compensation payment of 60 EUR and a market price of -90 EUR).

Illustration 7

Illustration 8

market price = -90 EUR | Ms. Solar | Mr. Trader | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Enter your text here... | revenue w/o curtailment | revenue with curtailment | revenue without curtailment | revenue with curtailment | value of curtailment |

Payment from Ms. DSO | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Power payment from Mr. Trader | -90 | -90 | 90 | 90 | 0 |

Compensation payment from Mr. Trader | 0 | 60 | 0 | -60 | -60 |

Market revenue trader | 0 | 0 | -90 | 0 | 90 |

Curtailment cost trader | 0 | 0 | 0 | -10 | -10 |

Sum | -30 | -30 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

Note how despite spot prices being paid instead of reference market values, the final columns in the table are the same as in the reference market case above i.e. the choice payoff by Mr. Trader has not been changed. The revenues of both parties, Ms. Solar and Mr. Trader in both cases, however, have changed dramatically. In a reference market logic, the revenues of the producer are always fixed at a certain level, irrespective of hourly prices. However, the revenues of the trader differ accordingly with prices, as they receive variable prices but pay out fixed prices. This changes in Spot prices contract, where now Ms. Solars revenues fluctuate on an hourly basis, while Mr. Trader's revenue is always zero, as he simply passes prices on to Ms. Solar. Surely, in cases of negative prices, Ms. Solar is clearly worse off than in a reference market price scenario as in one she receives the fixed price whereas in the other she has to pay negative prices for her production. However, keep calm, there is no black magic going on. Ms. Solar suffers at negative prices, however also benefits much more when prices are positive. In the previous graphs prices were picked to average out at 30 EUR/MWh i.e. exactly the same level of the reference market value. The following graphs sketch out Ms. Solar’s and Mr. Trader’s revenues in a spot price environment. One can see in the graph below that Mr. Trader’s revenues are always flat i.e. zero when there is no curtailment taking place. Ms. Solar’s revenues considered at different prices fluctuate more heavily, however over this range of prices her average revenue is exactly the same as in the previous cases, i.e. 90 EUR.

Graph 3: Revenues depending on market price levels

Summary

Through these examples, and I admit, it’s not the easiest read of all times, I have tried to illustrate some key points about the business logic of renewable curtailments.

- Economic curtailment choices should be made by traders as they face market prices and usually have asset control through their virtual power plant (VPP).

- The price at which a trader curtails an asset solely depends on the additional compensation payment to the producer and his curtailment costs. When there is no subsidy to compensate for (as in the §51 case) and if there are no curtailment costs, curtailment takes place at a price of zero.

- Contracts should be constructed so that producers are indifferent between being curtailed or not. This requires full compensation for foregone revenues. Producers do not make curtailment decisions. To have perfect incentive alignment the trader needs to receive the revenues/costs of curtailment decisions.

- If the conditions postulated hold, it does not matter whether producers are under reference-market contracts or under spot price contracts. Neither for the price of curtailment nor for overall revenues. The fact that producers receive (i.e. pay) negative prices with and without curtailment, does not make them worse off overall. This seems counter intuitive, however their overall revenues are maximized when contracts are structured this way.

final note: as you have been brave enough to read to this point I will spare you the §51 case with spot market contracts, because the overall logic does not change. If you are keen to have it, leave me a note.